A Poet and a Geologist’s Love Letter to Life Lensed Through a Mountain – The Marginalian

[ad_1]

How astonishing to remember that nothing has inherent color, that color is not a property of objects but of the light that falls upon them, reflected back. So too with the light of the mind — it is attention that gives the world its vibrancy, its kaleidoscopic beauty. The quality of attention we pay something or someone is the measure of our love. And because every littlest thing is, as John Muir observed, “hitched to everything else in the universe,” when we pay generous and unalloyed attention to anything, we are learning to love everything; we are learning that all around and within this world there is another, numinous and resinous with wonder, shimmering with a sense of the miraculous.

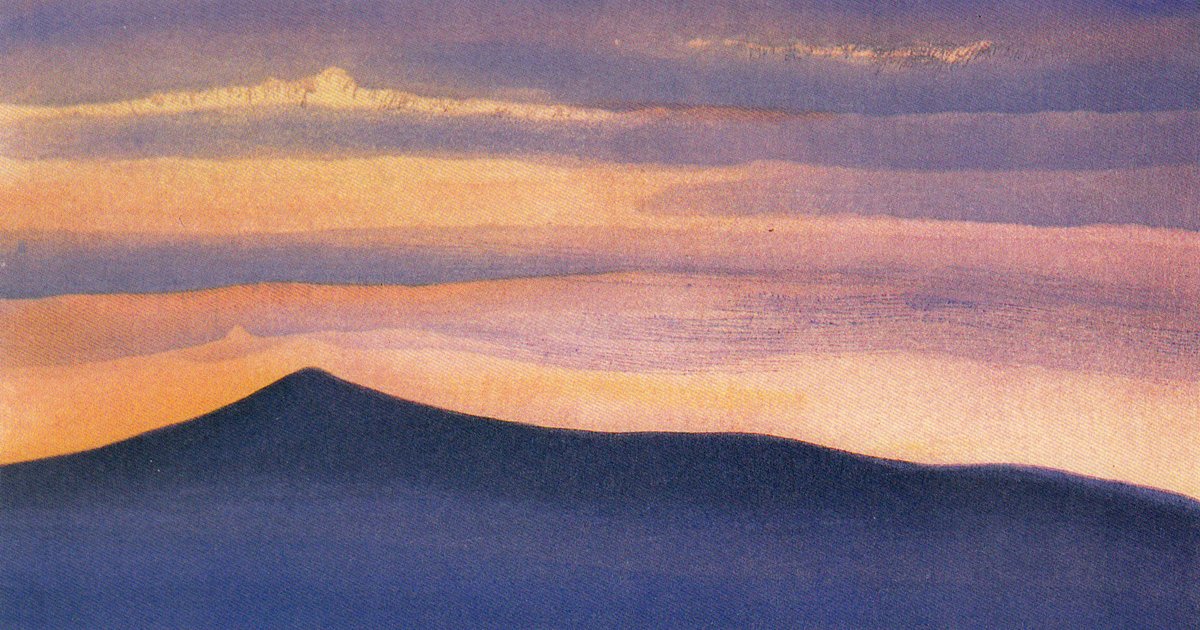

That recognition and its ample rewards animate The Paradise Notebooks: 90 Miles across the Sierra Nevada (public library) — the soulful chronicle of thirteen summer days the poetic geologist Richard J. Nevle and the Buddhist poet Steven Nightingale spent walking across one of the world’s most majestic mountains with their wives and teenage daughters, recording and reflecting on those devotional acts of pure attention in diary entires, essays, and poems that interleave science and spirit, observation and metaphor, grandeur and smallness. What emerges is a love letter to “a tender whole that is so much sweeter than the sum of its lonely parts.”

Nevle — who was first enchanted by the distant contour of the mountains when he was five but did not see them fully until he began his doctoral studies in geology eighteen years later — writes:

Many claim to have found God in the mountains. I don’t know what God is, but I admit to having sought her there too. Whatever my search, I have found that the pursuit of scientific inquiry — its own, necessarily limited kind of truth-seeking — can be as much an act of devotion as it is scholarly meditation. For to pay attention to the world, to seek its stories, to run your fingers along some crack of rock or furrow of tree bark, to admire a raptor in flight, to look, closely, at the construction of a previously unencountered wildflower — to wonder and to seek answers to how these things might have come to be in the world — are themselves acts of devotion, ways of knowing, ways of longing for communion.

Nightingale harmonizes:

Each world bears all the worlds we might find within it. If you understand one outcropping of stone, or one wildflower, or one hummingbird — if we see our way along the tracery of cause and effect, the mystery of change and recreation — then we are led to everything we see, and everything we are.

It is no accident that Virginia Woolf arrived at her epiphany about the unity of being while looking at a flower, that Oliver Sacks grasped deep time while walking in a forest, that Mary Oliver contacted the interconnectedness of life while observing an owl: It is beauty that beckons our attention, and it is attention that lets us see the world whole. Nightingale considers the common root of these experiences, these revelations of wholeness:

In most cultures, in every century, beauty is bound up with unity. Beauty illuminates the affinity, the inner relation, the resemblance, the kinship, the concord and identity of things. We are all trained to tell things apart. In the experience of beauty, we learn to tell things alike; to move from the darkness of oneself to a sympathy, an open rapport; a longed — for, conscious union with the world. Beauty is a lucid and graceful assembly of forms that calls the mind close to life, our bodies close to the earth, and all of us closer to one another.

[…]

There is nothing more powerful than the movement toward beauty. As we walked, this thought sustained us. What we needed was to keep moving: one more day, and in each day, all day, one more step. It struck me as the simplest rule of life and of reflection: keep moving. Stay in readiness. Cultivate openness, clarity, affection, an easygoing revelry of the senses, a trust in our luck that we are here on earth at all, that we have this moment at all. Movement along a trail is movement within the mind. In the long run, the revelation of beauty is not a matter of chance: it is the centermost surety in life.

Beauty matters because it swings open the doors of perception, and it is by seeing — by taking in what is there, incorporating it into our inner world — that we can begin to comprehend and connect, out of which the sense of belonging arises. Nightingale reflects:

This is true for everyone, wherever we are: what we see is the preface to what we can see. Beyond that preface, with work and love, is what we can come to understand. If we can understand, then we can live. In the Sierra, we understood that we might, after all, belong here with tree and rock and time and light. We might, for a brief spell of years, have the luck to find a home here by following the beauty that beckons us.

Observing the delicate fragility of a single ice crystal, and thinking about Wilson Bentley’s snowflakes, he adds:

The world around us is not what we see. It holds a life-giving, gift-giving, invisible order everywhere and always. It is an order of musical and exultant beauty. It has a mysterious and radiant splendor. Everywhere we look, if we would look, the natural world is making beauty, without fanfare, and the work is so plain, intelligent, playful, and devoted, that there is only one word for it: cosmic.

Throughout their journey, what kindles this sense of the cosmic are encounters with the earthly, in all its glorious smallness and specificity — a mountain chickadee hardly larger than a grape, singing in its “husky, harsh-sweet voice”; clouds “tangerine then crimson then lavender then gray”; a nutcracker harvesting ninety thousand whitebark seeds in a single year with its bill “black as obsidian”; a yellow-legged frog “as small as a baby’s hand, as still as a Buddha”; an aspen with its aria of color sung by chloroplasts that outnumber the stars in the Milky Way one hundredfold; a prairie falcon slicing through the clear blue with its speckled body, evoking a rush of astonishment that “such a wholly perfect thing could exist.” Nevle writes:

There is something numinous and joyful in these encounters, a way in which the boundary between the world we sense and the world that is beyond our senses becomes, for the briefest of moments, thin — almost transparent.

Punctuating the poems and essays are diary entries raw with aliveness. On the second day of the expedition, Nevle records:

Up too early again. Listening to the patter of rain dripping from the tree limbs onto the tent and the hush of the creek in the darkness. Breathing in the scent of earth and rain. I can’t believe we are here, surrounded by these old trees and mountains, with days ahead of us. I’m a little boy all over again, incredulous that this place actually exists, and I am here in it. I want to get up and wander down to the creek and feel its black, wet, cold aliveness on my skin.

That exhilaration emanates from a sudden and vivid sense of the interconnectedness of life in the mountain, the interbelonging of the wanderer and every wild creature, every rocky crevasse:

The great spine of rock holds diverse forests, dreamy meadows, skeins of streams, radiant lakes, and rare glaciers. Life ascends even to the highest reaches of the range, thousands of feet above tree line, where gardens of black, orange, and chartreuse lichen adorn the rock. Everywhere a tenacious living skin sheaths the ancient bones of the mountains.

[…]

The gray-crowned rosy-finch, the bighorn sheep, the pika, and the skypilot with its violet-cobalt blooms make their home among the enchanted stone that air and dust and time and life made possible.

Moving through the mountain, Nightingale embraces the poet’s task of wresting metaphor from observation. In a reflection that calls to mind poet Natalie Diaz’s magnificent meditation on brokenness as a portal to belonging, he writes:

The mountains are whole and beautiful for one principal reason: they have been broken so often… It is the very breaking and jointing, the cracking and carving and breakdown, the weathering and scouring, that all together give rise to the countless forms of beauty — iridescent, miraculous, gift-giving, exultant — throughout the whole of the range.

But it is often the geologist who best channels the poetic dimension of the living world. A century and a half after Emily Dickinson gasped in a poem that “to be a Flower is profound Responsibility,” Nevle writes:

What do we know of flowers? Of their wiliness and brilliance born of a ferocious will to live? Of their ability to extract what they need to survive over their fleeting lives, only so it can be given away? Consider the genus of flowering plants known as Castilleja, the paintbrushes. Species of Castilleja occur throughout the Sierra, from the oak savannas of the lowland foothills to the fragrant conifer forests of the mid-elevations to the sky gardens of the alpine fellfields — almost to the very crest of the range — blossoming in flames of vermillion and violet and cream and silvery mauve. Valley Tassels, Owl’s-Clover, Wooly Indian Paintbrush, Great Red Indian Paintbrush, Hairy Indian Paintbrush, Subalpine Paintbrush, Alpine Paint-brush, to name just a few of more than a dozen species of Castilleja whose blossoms return each year to the mountains. The sheer variety of Castilleja species you might encounter in a single summer day of wandering the Sierra might be enough to make you weep with gratitude for all the world offers us.

In the epilogue, Nightingale reflects on this countercultural endeavor to reunite dimensions of being that naturally belong together, that illuminate and magnify each other, despite how much our siloed and segregationist culture tries to keep them apart. (That, of course, is the animating spirit of The Universe in Verse.) He writes:

Science is thought by some to be dry, technical, and quantitative. It is not. Study is exaltation. Fact is miracle. Number is portal. Understanding is joy.

Poetry and spirituality are thought by some to be abstract, ethereal, private. They are not. Nature is language. Mind is sensual. Soul is earth.

Complement The Paradise Notebooks, an exultation of a read in its entirety, with The Living Mountain — poet Nan Shepherd’s timeless love letter to life lensed through the Scottish Highlands — and poet, painter, and philosopher Etel Adnan’s poignant meditation on time and transcendence lensed through Mount Tamalpais, then revisit Emerson on nature and transcendence and Steinbeck (in his little-known nonfiction I find even more excellent than his novels) on wonder and the relational nature of the universe.

[ad_2]

Source link